From Curtsy to Controversy: A Woman Soldier in Elizabethtown

- Denise Rompilla

- Mar 24, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Mar 25, 2025

The American Revolution, like many great causes historically, attracted a range of

selfless people ready to put their lives aside for what they believed in. Revolutionary-era women even more so, as dedication to the cause for them often meant contribution only within the confines of gender normativity. Some women, however, made their impact felt through more audacious, extralegal means. Consider the subject of our letter "Lady Elizabeth" as we'll call her, Margaret Cochran Corbin, or Deborah Sampson, women who ventured to the front lines in male guise, contra popular social custom and braving the low odds of the greater cause.

“And for what?” you may ask, understandably so. Women supporting the cause often saw their efforts go under-publicized or even criticized by the men and media of their time. But while the view of political participation as an 'unwomanly' activity

prevailed, women were, after all, equally as affected by Parliamentary taxes as the men, outraged by the British occupation of their homeland, and had their families torn apart by war.

As such, Patriot women persisted in supporting the colonial cause despite these societal

barriers, steadfastly contributing however they could. Engaging in public campaigning,

fundraising, boycotting British goods, spinning bees, performing domestic work at war camps, working as nurses, or even the occasional enlistment. Their efforts not only demonstrated support for their sons and husbands at war but a larger, patriotic belief in the potential of the revolution itself.

An instance of the great resolve of Patriot women is wittily captured in Esther De Berdt

Reed's broadside "Sentiments of An American Woman" writing: "Our ambition is kindled by the flame of those heroines of antiquity, who have rendered their sex illustrious and have proved to the universe that if the weakness of our Constitution, if opinion and manners did not forbid us to march to the glory by the same paths as the Men, we should at least equal and sometimes surpass them in our love for the public good", declaring that women’s participation in the Revolution was, in part, a continuation of the efforts previous great women made for the public good. And if it were not for the limitations of social custom and their physicality, women would not only match men’s efforts but surpass them.

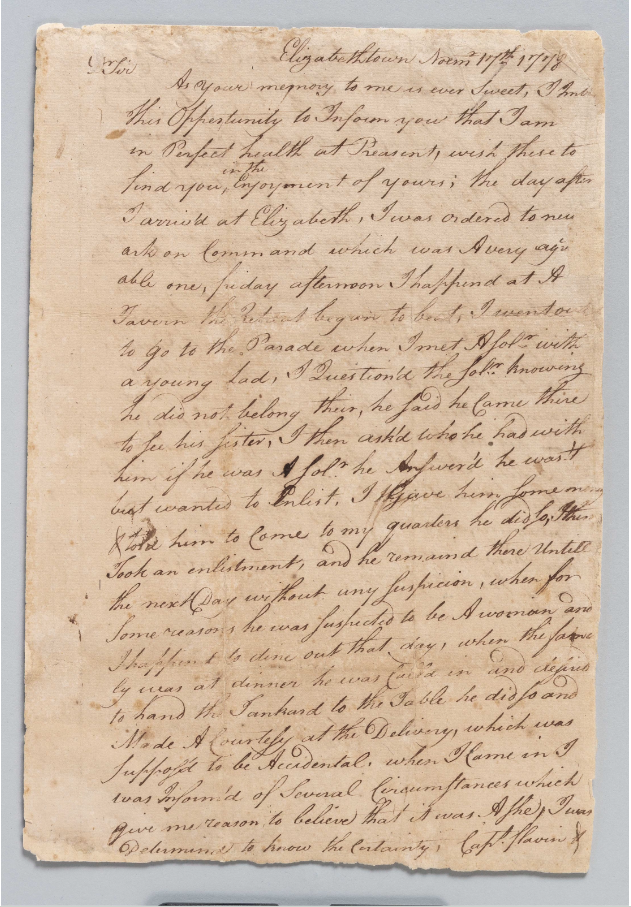

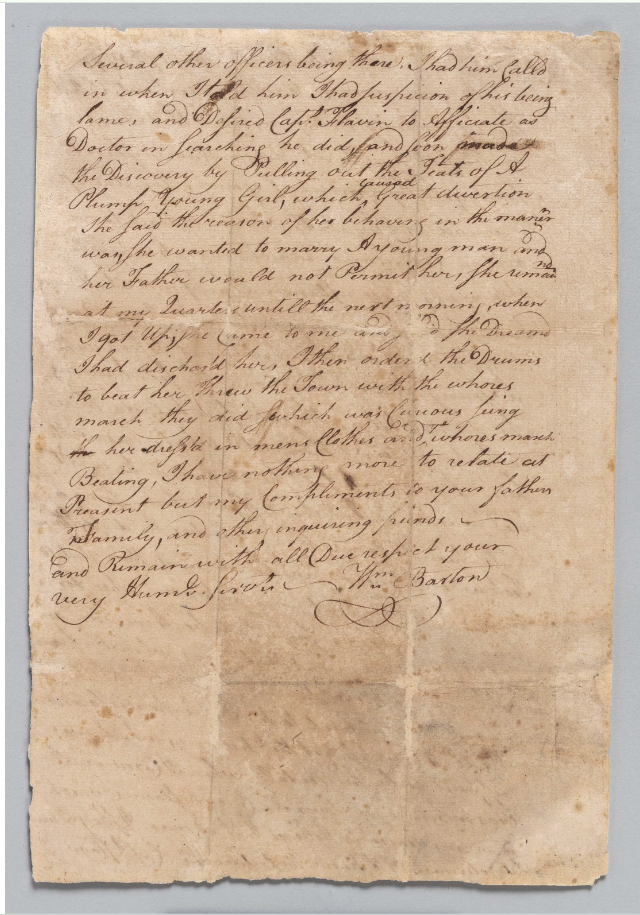

To that end, women like Lady Elizabeth strove to test those limits. An account of her

story, described and potentially adulterated in a letter written by Officer William Barton,

in 1778, demonstrates the scope of her actions and the repercussions she endured for them. When Barton personally enlisted her, Elizabeth made it past the first-line screening, but, suspicion of her developed after Elizabeth curtsied while serving a tankard at dinner, a classically effeminate gesture she brushed off as accidental. This curtsy, and the growing distrust of Elizabeth from army corporals, led to Barton and his officers conducting an intrusive physical examination, revealing her to be a woman. In the end, rather than applauding her bravery, Barton subjected her to public humiliation, ordering her to be marched out of the camp to the "Whore’s March," a dismissal steeped in misogyny and an unfounded assumption about her character.

When found out, Lady Elizabeth explained her reason for enlisting as seeking a young

man to marry, as her father had forbidden her from wedding. This reason, if we take it to be what she actually said and not reinterpreted by Barton, likely was given not to sincerely describe her motivations, but as a meek deflection to avoid any further harassment from the corporals. For one, enlisting in the Continental Army as a man would have been an unnecessarily arduous, deadly, and counterproductive method to pursue marriage. Secondly, if she had the freedom to leave her father’s home and assume a male identity, she likely also had the autonomy to escape her father's control and seek marriage through other, less perilous means. In actuality, Elizabeth,

as a woman who had just had herself invasively revealed to a group of men, was likely searching for a soft-hearted and disarming explanation for her enlistment, one that might deflect scrutiny and prevent any further ire or punitive actions against her.

Further, while her explanation somewhat aligns with the idea of the camp follower, a

married woman who would trail the army to support their enlisted husbands, she mentions no such connection, but rather, the quest for a suitor. Instead, the day

after already being caught, she confessed to having a dream of being discharged from the army to Barton, which suggests that her enlistment may have held significance to her in a way related to ongoing service, rather than partnership. Though we cannot know her true motivations with certainty, as we have no knowledge directly from Elizabeth’s perspective, between looking for marriage amid a war, and a subtle desire to continue her enlistment, it is far more reasonable to interpret her actions as those of a woman seizing agency in a society that denied her formal avenues of participation, rather than as a romantic escapade in defiance of her father.

Though Lady Elizabeth’s story ends rather tragically, she was one of many cross-dressing revolutionary women. There were also those like Deborah Sampson, whose valiant defiance of gender norms led to public recognition, and even public speaking tours post-war. Sampson, motivated by Patriotic-sympathies, made an initial attempt to enlist as a man and was caught (Museum of the American Revolution, 2018), but soon after made another attempt under a different identity, which that time went undetected for nearly two years. Subsequently, her bravery earned her recognition post-revolutions, including a military pension, being one of a few colonial women soldiers to be awarded one. Today, Sampson’s story is remembered as a historic triumph for women’s political

participation and a testament to the possibilities that arose when women’s determination

outpaced the societal mechanisms designed to confine them.

With this being said, success stories like Sampson’s were the exception rather than the

rule. Women like Elizabeth and others who failed to evade detection faced punishment that was deeply gendered and often demeaning, reflecting society’s anxieties about female autonomy. Their enlistment despite the odds, illegal, dangerous, and socially condemned, demonstrates if not a desire to transcend their prescribed gender roles, then a display of their genuine, selfless patriotism. Unlike Sampson, whose heroism has been immortalized, Elizabeth’s legacy exists only through Barton’s letter. Yet both women’s stories demand recognition, not just as isolated acts of defiance, but as part of a broader revolutionary spirit that extended far beyond the battlefield and into the social fabric of womanhood in the revolutionary era.

Primary Source: Letter of Discovery of a Female Soldier, 1778, New Jersey State Archives

Comments